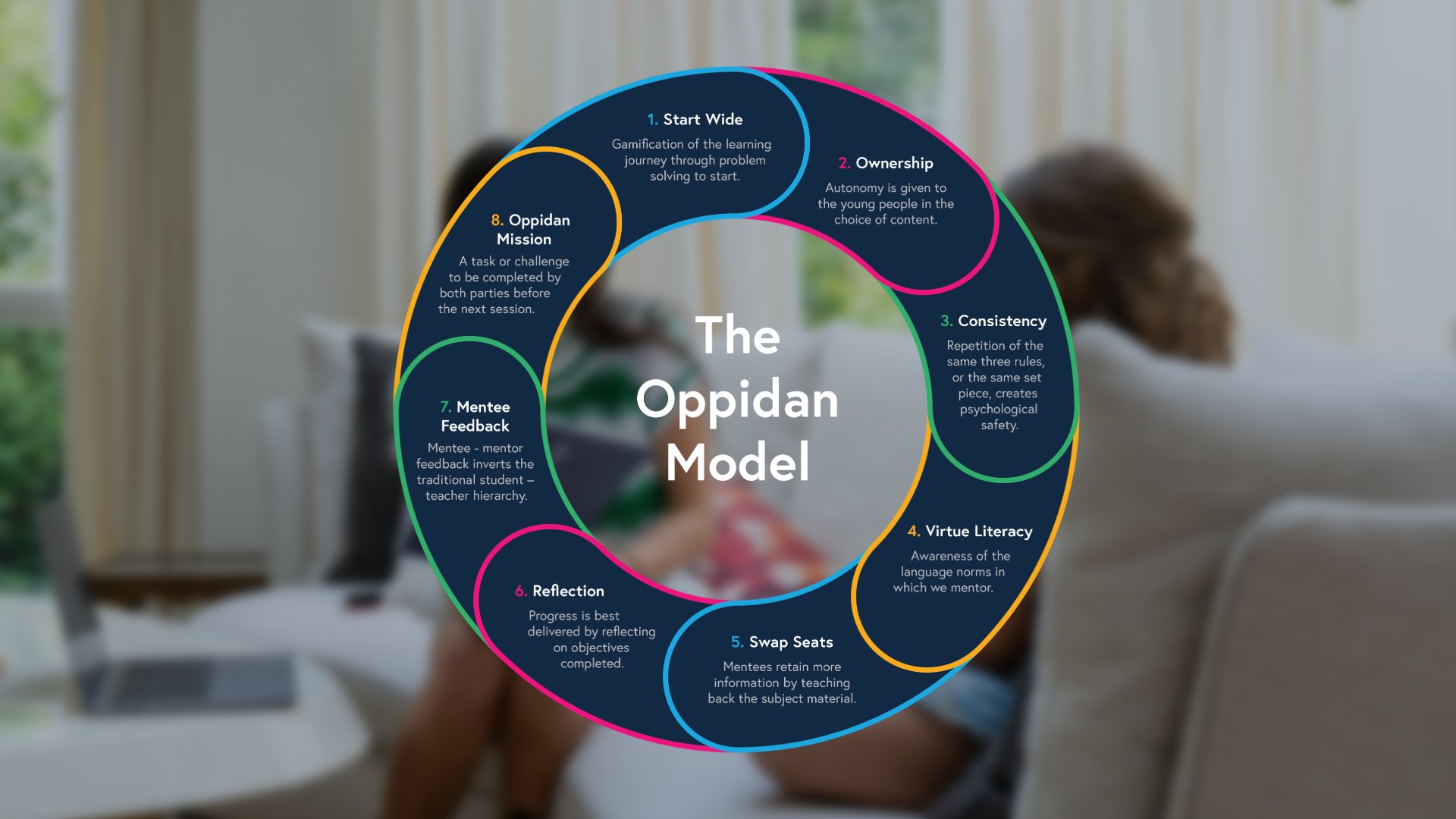

The Oppidan Model: how we mentor

For the last ten years, we’ve been researching and testing the best approaches to delivering one-to-one support for young people.

From the practical – how you both sit, organise your desk – to the conceptual – how you create autonomy, prevent dependency, the research has always been iterative, and it’s been student led. We ask what works and what doesn’t and then build those ideas out with our mentor team.

The result is this: the Oppidan Model – one hymn sheet, a framework built to provide impactful support for young people and consistency in our delivery across hundreds of people.

We’ve outlined the research below, but it isn’t rocket science; you'd see many of the set pieces in any good learning environment the world over. The eight interconnected tenets of the Oppidan Model serve to provide the foundations for learners to flourish; guided by the more experienced mentor - the magic ingredient between family and school for a young person. Key tenets of our mentoring sessions are the same whether we’re helping a 10-year-old with their 11+ or an 18-year-old applying to university.

So what do these set pieces look like in practice and why do they matter?

1. Start wide

Beginning with a broader perspective is key to hooking kids from the start. The Oppidan Model allows us to home in on the three types of engagement coined by Fredricks et al. (2004): behavioural, emotional, and cognitive - three engagement approaches designed to maximise learning outcomes. Our first principle, Start Wide, also introduces gamification elements into the learning journey through problem-solving activities. Deterding et al’s (2011) studies found that problem-based learning combined with game elements significantly improve both engagement and knowledge retention; our mentoring sessions are structured to combine both elements. By framing learning as problem-solving, mentees become active participants from the outset, setting the stage for deeper engagement.

2. Ownership

Our second principle is all about empowering through autonomy and is based on the research around intrinsic motivation. Sharath Jeevan’s book ‘Intrinsic’ (2021) showcases the three tenets of intrinsic motivation in young people: mastery, purpose and autonomy and ownership is the cornerstone of our framework. When young people are given the keys to make the decision themselves, whether that be the choice of mentor they have, or in this case, the choice of content within the session, research and experience illustrates that young people are more engaged in the outcomes.

3. Consistency

Consistency builds trust through creating psychological safety. Studies show that when learners operate in predictable environments, their cognitive resources are freed up for deeper learning rather than managing uncertainty (Edmondson, 2018). We see this play out daily in our mentoring sessions in schools and at home – our session set pieces are key to helping mentees feel at ease and comfortable taking risks in their learning.

This might involve, for example, doing a “kindness break” where we ask the students to go and so something kind (give their mum a hug, lay the table), or doing the Oppidan Daily Do at the beginning of each session. It might involve spending 5 minutes every time looking at a story from the news, or a 5-minute presentation they do at the end of every session. Whatever the mentor and mentee choose, the consistency of exercise or set piece is crucial to creating familiar, trusting spaces.

4. Virtue literacy

Our fourth principle, virtue literacy is all about developing language awareness and setting key norms around the language used. Language consistency further supports the building of psychological safety through establishing language norms within our mentoring relationships. It is crucial that we build mentees’ understanding of the uniqueness of the mentor-mentee relationship. Sessions not lessons, the Oppidan Mission rather than homework and mentor not tutor are some key language norms which help build mentees’ understanding of the different role their mentor plays in their learning to their teacher, parent or friend.

5. Swap seats

Our Swap Seats principle further differentiates our sessions from the traditional student-teacher dynamic by Inverting traditional hierarchies. When we ask mentees to swap seats and teach a concept back to their mentor, we stretch mentees’ oracy skills whilst also gauging their retention and understanding of the session. We often see mentees light up at the chance to teach a concept back to their mentor and feel real pride in their knowledge base.

6. Reflection

We want mentees to leave us with strong self-awareness and a toolkit for learning which gives them all the personalised tools they need to support their own metacognitive processes – essentially do young people leave us with an understanding of how they learn best? Time for deliberate and carefully scaffolded self-reflection is key in order for each young person to build their own personalised toolkit and relies on strong self-awareness. Research shows (Kolb, 1984; Gibbs, 2010) that structured reflection can significantly improve learning outcomes, lead to stronger metacognitive skills and better long-term retention. So you’ll see structured self-reflection time in every Oppidan mentoring session at home and in all our schools. We also ask students to flex their reflection muscles and give targeted feedback to our mentors at the end of each session, allowing us to improve our next sessions in line with mentees’ needs.

7. Mentee feedback

We also ask mentees to give their mentor feedback at the end of each session. Research by Hattie (2009) shows that reciprocal teaching approaches like our Swap Seats have a strong positive impact on student achievement and we see this play out regularly in our mentees’ academic progress.

8. Oppidan Mission

Our final principle, the Oppidan Mission, creates the opportunity for further stretch and challenge beyond the session, nurturing learner curiosity and autonomy too. Research shows that structured between-session tasks can improve learning outcomes (Zimmerman, 2008). Maintaining learning momentum through specific missions reduces the forgetting curve (Ebbinghaus, 1885). Our missions are specific to mentees’ interests and strengths and allow young people to further stretch themselves once their session ends. From building their own rocket with nothing but landfill waste to performing a monologue to stretch their presentational skills, our mentees continue to surprise and delight with their curiousity and creativity. Our missions also help families get involved with our mentoring too – we've even had a whole family record their own Shakespearean sonnet recital!

None of these eight components are unique or pioneering approaches to teaching and learning. What we feel makes the Oppidan Model particularly effective is how these eight principles work together to create a consistent and comprehensive learning environment irrespective of whether mentees are working on their character, speaking, skills or even improving their subject-specific knowledge. Our model's integrated approach creates the foundations for a self-reinforcing cycle of engagement and achievement. We continue to train regularly as we work to further develop mentor confidence in implementing the Oppidan Model into all sessions. We are also using the opportunity provided by our new remote learning platform, Lessonspace to conduct supportive lessons observations at scale so that we can review and reflect on our practice and continue to evaluate the Oppidan Model’s impact on our mentees.

References

Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. 2000, 'The "What" and "Why" of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior', Psychological Inquiry, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 227-268.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R. & Nacke, L. 2011, 'From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining "Gamification"', Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, pp. 9-15.

Edmondson, A.C. 2018, 'The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth', John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Fredricks, J.A., Blumenfeld, P.C. & Paris, A.H. 2004, 'School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence', Review of Educational Research, vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 59-109.

Gibbs, G. 2010, 'Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods', Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Hattie, J. 2009, 'Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement', Routledge, London.

Kolb, D.A. 1984, 'Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development', Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Mercer, N. & Dawes, L. 2014, 'The Study of Talk between Teachers and Mentees, from the 1970s until the 2010s', Oxford Review of Education, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 430-445.

Wang, J., Zhang, Y. & Yin, H. 2020, 'Investigating the Effectiveness of Multi-component Educational Interventions: A Meta-analysis', Educational Research Review, vol. 31, 100369.

Zimmerman, B.J. 2008, 'Investigating Self-Regulation and Motivation: Historical Background, Methodological Developments, and Future Prospects', American Educational Research Journal, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 166-183.